Cato Institue forum, June 11, 2019

This is the first part of a four-part transcription of a Cato Institute forum (Hayek Auditorium, June 11, 2019) that was moderated by Doug Bandow (Senior Fellow, Cato Institute) and featuring Heidi Linton (Executive Director, Christian Friends of Korea); Randall Spadoni (North Korea Program Director and Senior Regional Advisor for East Asia, World Vision); and Daniel Jasper (Public Education and Advocacy Coordinator for Asia, American Friends Service Committee).

Heidi Linton, Randall Spadoni, and Daniel Jasper have first-hand knowledge of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). Their organizations maintain long-term aid programs in North Korea, and all three have spent time there as part of humanitarian missions, including trips to parts of the country closed to most visitors.

In the discussions that follow they offer valuable insights from their experience of working in the DPRK. This is at a time when lack of understanding by U.S. policymakers of what North Korea is, or how it operates, may be hindering Washington’s ability to peacefully resolve the crisis in its relationship with Pyongyang.

The NKhumanitarian team has transcribed the forum discussions for the benefit of our readers. It is in four sections:

- Part 1: Daniel Jasper (American Friends Service Committee)

- Part 2: Heidi Linton (Christian Friends of Korea)

- Part 3: Randall Spadoni (World Vision)

- Part 4: Questions & Answers

Some very short sections of the interviews have been omitted from the transcription if they are speech mannerisms or a phrase that was repeated more clearly immediately after. These omitted sections are flagged with ellipses in the text below.

Except for that proviso, the site editors have tried to accurately relay the exact discussions as they took place during the forum but there may be some other, very minor, discrepancies.

Part 1: Transcript of Daniel Jasper’s presentation. He is the Public Education and Advocacy Coordinator for Asia for the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC). In his presentation, Mr Jasper:

- Provided a brief summary of the AFSC’s work in Korea;

- Highlighted the value of exchanges and trust building exercises between North Korea and the United States for the purposes of achieving broader humanitarian goals;

- Explained the challenges for delivering humanitarian aid created by travel restrictions and sanctions imposed by the United States, the United Nations and broader international community;

- Recommends….

[History of AFSC in Korea] I’ve been to North Korea twice, once in 2016 and once in 2018 and that’s mainly because my role is really geared towards Washington DC and representing our programs here in DC. So I’ll gear my comments a little more towards the policy arena and just how we’ve seen some of the impacts of recent rules and regulations and policy changes impact our work on the ground.

Like I said, I’m Daniel Jasper of the American Friend’s Service Committee Public Education and Advocacy Coordinator…. I just want to touch on AFSC’s history in North Korea. The organisation itself has been around for about 100 years.

In Korea we entered South Korea in 1953 almost as soon as the ink dried on the armistice. We were there, we were one of the first organisations to respond to a call from the United Nations that was asking NGOs for assistance in reconstruction efforts. And so we were there for about 5 years doing reconstruction. We helped reconstruct hospitals and houses and things of that nature and that program wrapped up, as planned, 5 years later in 1958.

We stayed engaged in the region, however, and in the decades that followed we noticed that there were considerable issues … a few staff members attempted to enter North Korea and they were successful in 1980. They were the first representatives of a U.S. public affairs organisation to enter North Korea and that kicked off a really, really productive relationship with North Koreans that has lasted all of the political situations that we’ve seen up until today.

[AFSC organised exchanges between the U.S. and DPRK] For about 15 years we were primarily doing exchanges and we would basically take North Koreans to the United States. We would take delegations of Americans to North Korea.

And I point out this picture … of the North Koreans with an AFSC staff member in front of the Liberty Bell. It’s not something you see every day but, actually, this was fairly commonplace throughout the 80s and early 90s!

This was done primarily with the understanding that we were engaging for dialogue’s sake; that we wanted to understand the other side’s point of view … [there] wasn’t necessarily a direct program goal in mind but this trust building, these engagements, really did lead to something more important.

[Work of AFSC in the DPRK] In the mid-90s, when North Korea experienced the famine, ASFC staff were some of the first international professionals that were able to bear witness and that were let in [to see] what was happening on the ground. And so they immediately returned home and put out calls for aid and started to raise alarm bells in the international community. And that [the ability to travel to North Korea] was born, mainly, from doing exchanges.

As the famine subsided it was recognised … [by] AFSC staff that food security was an integral part of this conflict [between North Korea and the United States] and it was also something that we could contribute to directly. While we were not an agricultural organisation, we understood that it was something that we could help with in the interim while we build connections towards a larger peace.

You’ll see a picture [that’s] a very typical picture of a monitoring and evaluation trip that we do. We usually go twice a year and we go to the rice fields and do all sorts of things in terms of pilot projects, trying to raise agricultural yields, primarily with rice. That has gone on for, I want to say upwards of a decade, but with recent policies in place this has been very difficult to do on a regular schedule as we have done before. So to touch on a few of the impacts [of] ‘maximum pressure’ [from sanctions], they typically fall into two direct categories, two buckets.

[Impact of travel restrictions] One is with respect to the travel restrictions that have been put in place. In September of 2017, the State Department invalidated U.S. passports for travel into or through the DPRK or North Korea. This is an issue for, I think, many people especially in the humanitarian realm.

The regulations do offer four exemptions. So you can get what’s called a special validation passport or sometimes it’s referred to as a ‘waiver’ in the press. [This is available] … if you are a journalist, a staff member of the International Committee of the Red Cross, or you are going for compelling humanitarian reasons. Or there’s a fourth, sort of ‘blanket clause,’ that refers to ‘national interests’ that is left vague – probably for a number of reasons.

These regulations essentially make timing our delegations extremely difficult. Applying for these passports can vary. The response can vary anywhere from 5 days to 55 days. And so when you’re planning a number of things, it’s incredibly difficult to gauge, ‘when do we start applying for a passport?’ especially when we need information from our North Korea counterparts…. [The North Koreans] are not necessarily ready to give that information and so it’s a very ‘touch and go’ system at this point. This year it looks like that, due to the timing of all this stuff, we may not be able to go on our Spring delegation.

Last year, in fact, during the Fall, was the first time we were not allowed to go to the DPRK and that was due to the decision by the U.S. State Department. It was the first time either side didn’t allow us to since 1980 – and that was a decision by the U.S. side. I want to underscore that.

…. Prior to these travel restrictions it’s worth noting that there were about 1000 U.S. travellers per year, which isn’t much, but it’s probably more than most people assume. And there were actually 200 U.S. citizens living in North Korea, which is surprising I think. I wasn’t actually aware of that until after the regulations were put in place! And many were doing humanitarian work or even just day to day commerce activities. But they were doing so because they had religious convictions that they wanted to see the humanitarian situation improved in the country.

[Impact of sanctions] The second bucket that’s really impacted our work is, of course, sanctions. Sanctions have always been an issue for U.S. NGOs operating in North Korea. Sanctions have been in place since 1953 so there’s always been some interference. But prior to 2017, the situation was much better than it is now – it was not perfect but it was much better than it is now.

And it’s worth describing what U.S. NGOs and how they operated. Prior to 2017 we operated under, what was called, the General Licence … essentially guidelines issued by the Treasury Department that say ‘if you fall within these activities go ahead, do your work, you don’t really need to contact us unless you have some questions’.

Today, the only activities that fall under those [General Licence] guidelines are sending strictly food or medicine. And this is problematic, mainly, because most organisations don’t ship strictly these goods. If you’re shipping [medicine] with a hypodermic needle in it you will need, what’s called, a Special Licence because it has metal in it. And, typically, that’s the most important part, is the needle.

The Special Licence process is something that you have to go through with the Treasury Department that can take months to do. It’s a very lengthy application process, it requires the help of lawyers, and so essentially we’ve gone from processes that took us a few hours, to processes that take us many months to do and require expensive legal counsel.

This is obviously very problematic for when you’re trying to time shipments, when you’re looking at planting seasons versus harvest seasons – it’s nearly impossible to time it, in the way that we have in the past.… Many of the materials that AFSC ship are plastic and they are non-sanctioned items. However, non-sanctioned items still require a Special Licence from the Treasury Department – the process I’ve just described.

Things that we send are typically plastic rice trays. This was a project that we introduced to North Korea in 2007. And you’ll see a picture of it here. There’s a poster of a man carrying a rice tray and these trays are pretty simple in nature. It’s where you start rice seedlings.

So when they’re ready to be planted or transplanted, you [just] pop them out of the trays and throw them in the fields. It’s a very simple innovation. Typically the way that it’s [normally] done is that you start the seedling in the ground. And then when [the seedling] is ready to be transplanted you pull them up and you throw them in the rice paddy. When you pull [the seedlings] up it tears at the root and it can really injure and reduce harvests significantly. And so these plastic trays improve yields by about 10-15% which is significant for a country that’s facing major food security issues.

However, these items can’t be shipped without a Special Licence. Again, that takes many months. Recently, the UN issued a report, it was, I think, called the Rapid Food Security Assessment. They outlined many of the issues that the country is facing. They highlighted that 10.1 million North Koreans are food insecure at this point and then they went ahead and listed some of the items that are needed in this moment. And some of the items that are needed are these plastic [trays], plastic of this nature, plastic sheeting and things like that, that can help increase yields. But unfortunately, this is the type of stuff we would [normally] have no problem shipping immediately to respond to calls like this. But given the current regulations we’re not able to do so.

[Other AFSC humanitarian activities including family reunions and locating POWs and MIAs] …. I often mention a basket of issues that are sort of adjacent to the AFSC in that we’ve always kept an eye on and promoted, that are of the humanitarian nature, and that could be carried out today if both governments agreed to it….

The first one is reuniting families. Most people have heard of the reunions of South and North, but most people forget that Korean Americans are also part of this story. There are largely two groups of Korean Americans that have family in North Korea. There’s a group that often knows where their families are and could just go if there weren’t travel restrictions in place. And then there’s a group of families that are still looking to find their families and need sort of a match system similar to what the North and South have. This is something that is incredibly important especially in this moment. These families aren’t getting any younger and this is a great way to bridge diplomacy in the interim between large diplomatic events or summits. This is something that’s a great exercise for diplomats to carry out.

In a similar vein, after the Korean War about 7,000 U.S. POWs [Prisoners of War] and MIAs [Missing in Action] were … [unaccounted for]. We think [the remains of] about 5,000 of them are still in the North. We’ve promoted military to military cooperation to find those remains and to bring them back to the U.S. for identification. There are many family members that are still wanting to know what happened to their families, or their uncle, or their father … [who] are very interested in this. You may have noted that last summer the North Koreans returned 55 sets of remains. This is what I’ve heard from both North Korean and U.S. officials: [the officials] say [this is] the most successful cooperation … to date because it is actually kinetic; it actually gets officials in the room to work through logistic issues. It’s something that puts [discussions] into practice. However, that’s been relegated strictly to the militaries…. [This] is fantastic, but our diplomats lack a similar exercise. That’s why we say: right now is a great time to think about reunions [because U.S. diplomats can meet North Korean diplomats].

Lastly I’ll just mention really quick, international exchange programs are something that we think the North Koreans have been really interested in in a long time, and we think that you can go a long way in introducing them to international standards through things like [international exchange programs]. Particularly, there’s a program called the International Visitor Leadership Program. I’m a little bit biased, I worked on this program prior to my current job, so I really promote this program no matter what I’m talking about! But particularly in the case of North Korea, North Koreans are the only country, as far as I understand, … that was not participating in this program. That’s a real issue when communication is low and so this is sort of a ‘low-hanging piece of fruit’ that we really think policy makers could seize on.

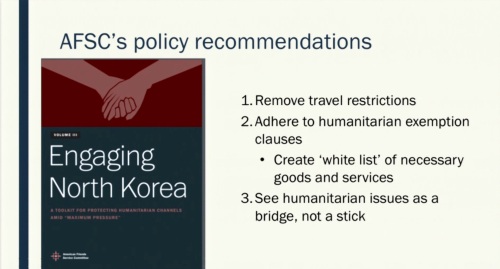

[American Friends Service Committee Policy Recommendations] Our [American Friends Service Committee] policy recommendations are probably fairly evident at this point!

We’d like to see the travel restrictions moved or at least modified significantly to allow some family members to travel; to allow a little bit more human to human contact.

We would like to see, and the way I said it here, ‘adhere to humanitarian exemption clauses’, and I stated it like that because every piece of legislation and UN Resolutions that have to do with sanctions with North Korean state that it’s not supposed to interfere with humanitarian operations. From our understanding, from AFSC’s standpoint, we think that it has not been adhered to within practice. So policy makers could do a lot in tweaking these regulations to streamline these processes. And it’s worth noting that North Korea is not the only place in the world that’s facing humanitarian restrictions and we’ve begun to have conversations with policy makers about something like a ‘Global White List’ that would essentially list goods and services that are required for humanitarian work around the world and would operate a little bit like what I mentioned – what was called the General Licence, but at a global level.

Lastly, we’d like the U.S. side to really see humanitarian issues as a bridge not a stick. This isn’t [the] way – to turn off humanitarian aid – and try to change the North Korean calculus. We’ve seen that tried. It didn’t work. It’s very clearly a mistake [to use humanitarian aid to try to change the actions of the North Korean Government]…. I came across this quote by Henry Ford that I think really illustrates why this is so important especially in the policy makers eyes. Obviously, it’s important for our values but … Henry Ford said it best. He said if there’s any one secret of success it lies in the ability to get the other person’s point of view and see things from that person’s angle as well as your own. And it’s the people to people contact, humanitarian engagement that allows us to do that. That’s why it makes it so important.

[…] Part 1: Daniel Jasper (American Friends Service Committee) […]

LikeLike

[…] just want to mention some of the uniqueness of working in North Korea. Dan [Jasper – see his talk here] has already mentioned sanctions and Heidi [Linton – see her talk here] too. I don’t think […]

LikeLike